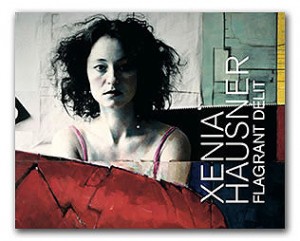

XENIA HAUSNER

FLAGRANT DELIT

Swiridoff Verlag, 2012

144 pages with 73 color Illustrations

28 × 22,5 cm, hardcover

French / German

ISBN: 978-3-89929-242-8

With essays by Rainer Metzger, Michael Haneke, Peter-Klaus Schuster and C. Sylvia Weber

Michael Haneke

Blind Date

What did they find out about each other beforehand? Why is she wearing gloves, dammit, and what is she looking at from between her leather-covered fingers? Why is the blonde guy below the Asian writing on that huge bus smirking so uptight? Is he still not able to accept the fact that he lost? What did the woman with the blue headscarf pull off that she can be so heartily and contagiously elated in all that drama that’s rising up out of nothing.

A Viewer gets a kick out of questions that cannot be answered because questions always approximate the complexity of what is seen, meaning life itself. And BLIND DATE is good for lots of contradictory and enriching question periods. A two hour film that’s been fit into a single moment. How fantastic!

Peter-Klaus Schuster

Ballet Russe

Xenia Hausner’s large-format painting, Ballet Russe (p. 31) is an artfully enigmatic image. Based on a photo, it depicts a young Russian costume designer at work in her Berlin atelier. Hausner turns the workshop with ironing-board, mannequin and patterns on a back wall from a real place into an abstract composition, a light-pink background framed in turquoise. On the right you see an orange-red right-angle, maybe a wall cabinet, on the upper left, a black circle. Cloth and paper patterns float like geometric color-field painting on the picture plane.

What do you really see in this photo turned color-intensive painting? The costume designer and her mannequin distort each other mutually. One thinks of clashes between articulated mannequins and people in works by Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst, where mannequins seem no less alive than humans. Xenia Hausner’s dressmaker mannequin, draped in paper and cloth, a collage of materials, takes on an animate existence. Meanwhile, the costume designer in a sleeveless, dark-green dress, her hair henna-red, only seems at first glance to be a young woman of flesh and blood with an erotic aura, leaning expectantly against the ironing-board and staring with her large shadowed eyes directly at the viewer. Suddenly you are shocked by the color of her skin. Those are no paint-stains from the stage-set. No, the young woman is herself a painted apparition, a fully artificial figure, her blue shadows and red cheeks clearly an allusion to images of the French Fauves. Their leader in things artistic was Henri Matisse, whose atelier paintings and pictures of upper-class apartments managed to alternate dizzyingly between real and abstract. Nowhere else but in the works of Matisse – the favorite artist of Russian collectors after 1900 – do interiors mutate so intensely into color compositions and then regain focus.

The title, Ballet Russe, refers of course to the ballets russes, Sergei Diaghilev’s famous ballet company, which triumphed on European and American stages between 1910 and 1928 and for which Pablo Picasso (as of 1916) and Matisse (in 1920) designed stage-sets and costumes. Here, in Xenia Hausner’s world, one gets to participate in an artful ballet played out between painting and photography, Matisse and Russian constructivism, fashion and modernity. The young Russian costume designer in Berlin becomes the personification of a transmedial spirit-of-the-age in which theatrical and vital productions clearly influence the young and creative and the youthful bohemian scene in the German capital at the beginning of the 21st century.