XENIA HAUSNER

talking to Günther Oberhollenzer

On 10 August 2012, during the preparations for the exhibition, Günther Oberhollenzer, curator at the Essl Museum, met the artist Xenia Hausner. The interview took place in Traunkirchen in Upper Austria where Hausner had rented a large workshop to work on the more than 8 m long painting Im freien Fall. Apart from general artistic questions and questions on painting technique, the conversation addressed significant themes in Hausner’s work, including the truth beyond the painted surface, the relationship between painter and model and the dramatic element in her work.

I would like to start with a question on your beginnings as a painter in the 1990s: what were the first reactions you got when you started to paint? What was the mood like in the art scene at the time in respect of figurative painting?

I didn’t really think about it, I simply started painting between doing two set designs as a kind of balancing exercise to compensate for theatre work which is very much conditioned by external factors. Basically it was a pretty muddled affair and quite playful. I painted two heads and then thought this is no good, I have to take a closer look. So I fetched a mirror and very naively painted my hand and my face as well as I could at the time. I immediately threw the first painting away. Later I painted my husband of the time, his children and close friends. There couldn’t be any reactions because for the first few years I simply worked behind closed doors. Then the pendulum swung out quite forcefully when people started to see the paintings. That was even before the “coming out” of the Leipzig School, and figurative painting wasn’t really “in” at the time. There were angry outcries and enthusiasm. It has always been that way, I am someone who polarises.

In his essay, Rainer Metzger wrote: “Despite its grim determination to maintain a relationship with the world, figuration is timeless, at best.” I think that is a good way of looking at it. On the other hand, figuration and the type of portrait you produce are often derided as “obsolescent”.

I am not right up-to-the-minute, but I am seismographic and I do reflect my time. I do not incorporate the latest evening news, but I very consciously live in today’s world. When I confront the canvas I have a rough plan, but that will change because the painting has its own defining personality. The painting doesn’t like this or that, it is obstinate, has a life of its own. When people ask me whether it isn’t very vain to hang up a painting showing yourself I always say: “This painting doesn’t have anything to do with you!” If it’s a successful painting, then it has its own personality, and if it’s a bad painting no one will want to look at it anyway. It drives me absolutely crazy when people stand beside their paintings – models often will – and are happy when others recognise them in a painting with several figures. I always say to them: “Go away. You look so trivial, it does you no good”.

It’s not good for the real person to stand next to the painted picture?

No, it’s not good for the real person at all, because the painting is a harder-edged truth seen through the subjective lens of the artist. The painting contains a metaphysical package, which the person doesn’t really possess in that sense. The person is a stimulant and an object of desire for the painter. What I am concerned with is an inner perception of a person, and that will always include the painter’s worldview. It is about interpretation, not about making an inventory. Klimt’s women look so magical, and when you see the photographs they look so commonplace in comparison because the paintings show them filtered through Klimt’s inner view and raised to a higher dimension. They were certainly intelligent and attractive women in real life, but this is simply something different.

Wieland Schmied wrote in an essay that with your paintings you intend to create the “whole theatre”, i.e. to create and stage “all of life” and not only the stage sets. Do you share this interpretation, which may be a little too heavy in terms of pathos?

I don’t see any pathos. He just used literary hyperbole to make his point. People like making those references to stage design to explain why I paint large formats. There are so many contemporary artists who paint large formats, so that explanation is too simple, but I probably have this dramatic side in me! Theatre explores human beings and so do I.

In an interview you once said that you were staging your “own dramas”.

I paint the subjects that I find within me and that I relate to. Every artist does that. When five people are hopping about in one of my paintings, I try to identify them by their inner essential core, although the story they’re appearing in is not their story. A classical portrait describes people in their own biographic environment. In my case the five people are cast like actors for a play. The play is “written” by me, and then I start looking for protagonists. They are acting in someone else’s biography and not in their own. I favour the hypothesis that there is no female or male aesthetics, only themes that people carry within them, and artists have the privilege of being able to spew them out. Paula Modersohn has addressed her wish to have a baby and painted many self-portraits showing her in fictitious pregnancy. Now you could say: “Look! Paula Modersohn does female painting!” Not true. In terms of style she may paint like the early Picasso, but her subject is a female concern. For Francis Bacon or David Hockney homosexuality is part of their life and therefore also something they address in their paintings. These are, if you like, the dramas each of us carries inside. In art they come to the fore and get addressed. Artists are not only autistic, they live in their time and they have a perception of the world which feeds into their work.

If one says that you stage your own drama isn’t there the danger of viewers expecting to see a story they can read? To me the paintings look more like fragments of a story.

Yes, they are fragments. It is not even my goal to present clear solutions, but to be precise in fragments. These fragments contain a sharpened or distilled message whose mystery I am unable to solve. The situations are not unambiguous, but the viewers can still read them because they are affected by them, they read the painting with their own resources given to them by life.

Isn’t it almost mandatory for some things to remain mysterious, since it’s often that very quality that makes the paintings fascinating?

Yes, I’m still a mystery to myself!

Visitors of our museum often want the guides to explain and decipher the paintings for them. But I think it’s terrific and fascinating that there are many things about paintings you can’t explain.

Go and explain the paintings of Neo Rauch, provide a set of “instructions for use” for them. Horrifying. You have to cast people back upon themselves and tell them everything that occurs to them is fine. The more mental processes are released by a painting the better. Everyone can invent their own story and that is just fine for me.

Are there times when the “staging” aspect that people perceive so often in your paintings is overestimated?

Quite right. There is a striking point, however: I need the “live moment” for painting, I have to really look at a dimple in the flesh or the curve of a cushion, and then a certain automatic drive will be set in motion. I really need the skin squashed on the windscreen, and I need to have the climber hanging from a rope (even if it’s with the help of the Traunkirchen mountain rescue service!). That is often very complicated in terms of reconstruction. But my painting thrives on that carnal moment which I see and translate. This does not apply to the basic idea for the painting, which is invented, but then it will be padded out with sensory input.

When Mrs Essl and we curators went to see you in your studio in Vienna in 2010, we were particularly impressed by the great lengths to which you go to prepare the setting for your paintings. We saw a full-size car that you had cut in half and taken to the studio. This stage-craft element is truly something special.

True, with others this would have been their finished installation! I have a workshop and need team members who prepare these things for me. In the theatre they call it “marking out the stage”. At rehearsals you don’t get the finished product but only the functional elements that the actors need to create their roles. I had placed the car under my skylight but then we had to shift it because of another painting. So we put it on castors and were then able to roll the whole thing around. We have perfected our system to work almost like in a theatre. I have also had someone from the Burgtheater come in and bring a harness and fix up the model with the harness. Now we need a mountaineer who explains to us how to handle the ropes (editor’s note: for the painting Im freien Fall). Dealing with such details will often lead to new ideas that develop from the precise research.

One can see in your paintings that they are the product of intense preparations.

I need this burrowing so typical of Scorpios. I have read how Robert Musil worked and asked a girlfriend of mine who is an astrologer whether he may have been a Scorpio. She found out that he was a double Scorpio. Musil always went forward and backward, took a brick out from the bottom, did it this way and that way, and ultimately this is what did him in because he was steamrollered by the zeitgeist. But zeitgeist or no zeitgeist – The Man Without Qualities is a fantastic book. This term zeitgeist, that so many are fond of, is often a source of artistic sycophancy.

We have now spoken about the setting. Another important factor are the models, of course. How do you find your models?

In a completely irrational way, and that makes it difficult, because I often find myself relating to someone without anyone knowing why. It is like falling in love. You don’t understand why two people fall in love; it is a mystery for outsiders. But even those on the inside don’t really know. It’s the same with me. I can’t really explain it, and I don’t even want to know. Helpful people often say to me: “Tell me what you need! Give me a rough idea of how that person is supposed to look.” Then I reply: “Forget it, send me to a place where there are a bunch of people and I will have a look around.” There is no rationale for it, I zoom in on something like a pig hunting for truffles. It has nothing to do with objective beauty or ugliness. I love travelling and take many photographs. Yet I don’t paint in the streets, but reconstruct the situations later. In one painting, for instance, there’s a bus that I saw in India. There they took me for a spy because I spent days in bus terminals and near the train station in Mumbai. There are paintings in which these photographs will then be incorporated. After having taken a photograph, there is the moment of reconstruction in the studio. Last year I was in China and they asked me to paint Chinese people. I can now find Chinese people in Berlin or in Vienna at the Naschmarkt (translator’s note: a large open-air market), and I can get them to my studio, building them into a situation I photographed back in China.

Do you usually have a basic idea for a story and look for motifs, or do you see a motif and develop a story around it?

It can go both ways. Whether a model sets an idea into motion or I assemble a crew for a certain idea, at some point I still need real people in my studio. I can’t fall in love with Prince Harry – unfortunately. Elizabeth Peyton or Marlene Dumas, both among my favorites, have another way of doing things. They don’t have to get involved in some realtity that confuses everything – at least not at the beginning.

To what extent will the model influence the finished painting? How much of the personality, wishes and thoughts of the models themselves ends up in your paintings, and to what extent are they projection spaces for your own experiences and feelings?

There are stage directors like Bob Wilson, who shows the actors exactly how to hold every single finger up to the light. Other directors like Peter Zadek make do with cryptic hints. Both methods produced interesting results. I am not hung up on either way and usually say “put yourself there and try it with your own body language”. That is a very creative chapter in the development of a painting and I go with the flow. I am open for what happens during the process of getting there on the basis of the photographs. My preparatory photographs are like a collection of material. Suddenly you see something that you didn’t know before and think “this is where it could go”. The notion that the model is a lump of lead, just sitting there and not even allowed to go to the toilet is absurd. The input is very important. I have read texts where models say they are slaves, like an object. That’s rubbish. Once they are in the painting I am as dependent on them as a dog on its master.

So you’re saying the models are empowered by their work?

They are a lot more powerful than they think. I often work with actors because they already have this playful creative streak, I can try out things with them. In the painting Liebestod I dealt with the death of my father. He is lying dead in bed and my sister is sitting in front of it as my alter ego. I got several men who resembled my father in phenotype to lie down on the bed for me, but it looked more like they were just dozing. Then I asked Peter Simonischek. He said: “Yes, I have played a few dead people.” He lay down – I had prepared the situation in terms of lighting and view – and then he asked me “You want it this way or that? I have played a few death scenes after all”. And then he offered me his repertoire of impersonating corpses …

Rather a spooky thought.

The process of mourning takes place somewhere else, but this situation at the studio is like a surgeon’s work. When you paint a naked body it is not erotic either. It is as erotic as a visit to the gynaecologist, which as a rule – unless he transgresses – is completely sober and focused on the technical aspects. When a painter paints a nude he focuses on coping with putting it on the canvas, even if he may later have a night of passionate love-making with the model or had one previously. But in the studio it is very clinical. And that’s what it was with Simonischek as the dead body. He was a totally creative partner. You do your grieving before and after. This is the way it is with death scenes, love scenes, nude scenes,… it is a bourgeois myth to imagine that the painter would stand there in rapture and get turned on.

Since you said the element of acting is important in your sessions: how do you go about painting portraits of well-known people such as Valie Export?

I paint large formats and invent stories, but I also explore the biography of a person in the classical sense of creating a portrait, as for instance in the painting of Renate Ankner, which we also have in the catalogue, since it fits in with the theme of mortality and survival or non-survival. She was fatally ill, and I have tried to capture her in that situation. Valie Export and her husband are a happy couple. I have tried to bring out this happy twosome – they are very different but deeply connected. I painted Heinz Fischer when he was still Speaker of the Austrian Parliament. In the background you can see the nicely classicist masonry of the Parliament building which he presided over at the time.

What distinguishes a commissioned portrait from a non-commissioned one?

Nothing at all in the final result, if everything goes well. The commissioned portrait harbours the danger that the artist might succumb to the wishes of the client, who is normally also the model, and start to be too docile or show a kind of anticipatory obedience. The commissioned portrait has a bad connotation, it includes the possibility of exploiting a weak spot somewhere along the line. The fee could make the artist submissive or compliant. The commissioned portrait is like any other portrait. You just have to take care not to cave in; the hare-lip needs to go into the painting. There are enough examples of that in art history.

I find it intriguing how you approach people in two ways: for your own narrative or in the classical sense of portrayal.

If you like, there are two types of paintings, but I always approach them in the same way. I try to understand or capture an inner essence. Either it’s the person in his or her own biography – which you would classically expect from a “portrait” – or it’s the person in an invented constellation. But once I have started painting it doesn’t matter anymore, I always try to get behind the facade.

You once described that as “the truth beyond the painted surface”. We briefly raised the issue at the beginning of our conversation that truthfulness and authenticity beyond the surface are important to you.

I am often scolded and derided for that truthfulness… I would like to call it an inner essence of people. I am driven by the urge to tease it out. As I’ve said, it is a matter of interpretation and not of stock-taking. In photography, in art photography that is, it’s also about interpretation, even if it’s a snapshot.

And when you manage to do that could we say that the painting is beautiful?

The painting or the person?

The painting.

The painting is meant to be good, not beautiful.

Is beauty a notion that plays a role in your art?

I don’t know about that. I think beauty is not so important. I am intrigued by interesting people, personalities, but not by beauty in the classical sense.

You’ve already mentioned Neo Rauch. According to him, the basic nature of painting consists “in putting a spell on a certain situation”. Painting triumphs, says Rauch, over the depicted object and in this way even something horrible or evil could become a highly vital work of art. Do you share this belief?

Absolutely. Ultimately, there is only the truth of painting – and it is stronger than the truth in life!

There are basic themes that recur often in your work: loneliness and love – whereby I have the impression that it is less about love than about the yearning for it or the loss of love.

Yes, those are themes I have in me. But don’t ask me why, I don’t really want to know.

Would you, then, consider your paintings melancholy or even pessimistic?

No, not pessimistic at all, perhaps melancholy, but also forceful, and that provides a balance.

You have frequently described painting as an erotic process.

Well, as a sensual process. If you really open up to it, painting shares aspects with being high on love.

Love and conflict are two extremes that are characteristic of your painting. I think that the process of painting – the intense exploration of the person in front of you, the relationship between painter and model, but also the battle with the material and the means of painting on the other hand – is deliberately left there to see on the finished canvas, for instance in the expressive colouring, the many red, green or blue tints on the skin of the figures…

True, I am interested in a spontaneous, vibrant element in painting. It makes me blow all my fuses. Those are the points that intrigue me most, where the painting itself contains a truth, the truth of creating – opening up to that; that’s an area where you can’t bullshit anyone.

But it is your intention that this process of creating should remain visible in the final result, isn’t it?

Yeah, I hope so!

What I meant is that not everything is smoothed over, with the initial struggle ultimately being camouflaged.

No indeed, that’s exactly what it shouldn’t be. You should be able to feel the effort, to leave the process of gestation open to view. In my work nothing is smooth and camouflaged; everything is relatively open and alive.

At the same time your sheer painting skills are remarkable. Even if your brush style seems free and spontaneous, I can’t help feeling that the painting process is rigorously organised and calculated. Every prop has its place, every colour is chosen deliberately, and nothing is left to chance. Am I correct in assuming that?

First of all I think of a picture. Then it comes into its own, stands up to me and demands something more, which I will then supply. That will often capsize everything. You always pay attention spontaneously in painting. At the end of the day what counts is that I capture this bicycle kick-stand or that face with my brush. I try to understand with the means of painting. In this context spontaneity plays an important role, and that communicates itself to the viewer.

A very striking aspect in your paintings is the colouristic brilliance. The colours are very strong, very powerful. How do you find your colours?

Not a clue. I just do. It is a bit like asking me, why are your eyes blue? Don’t ask me. A little murkiness is quite stimulating for creativity. If I were to rationalise every step in advance, I would probably be paralysed. At the moment of painting it has to be painting, and at that point I don’t want to reflect on how to put one foot in front of the other… the principle is always: doing, reflecting, doing, reflecting – I want to keep that spontaneity.

Is it difficult to find the right moment to let go of the painting and tell yourself it’s done now?

Sometimes not in the least, at other times yes. There are paintings where you struggle incredibly. But that doesn’t make them the better painting, nor the other way round. Some things are easy, others are very challenging … it’s a story of ups and downs, the paintings and I.

Another characteristic trait of your work is the combination of painting and photography. The boundaries seem to have been lifted: photographic elements appear in the painting, painted work is captured on photographs, photographs are worked on with paint. The popular term “mixed media” doesn’t really cover it, does it?

No, but I have dropped the habit anyway and often deleted this designation. In historical terms the terminology as such might no longer be correct. I have always taken photographs as a way of collecting material. Then I made a book with my working photos and painted an enlarged photograph into it. I continued to pursue this and at some point it gave rise to a kind of crossover thing between painting and photography. In the meanwhile, however, there is nothing left of the photographs. They basically prime the pump for the painting and are often sacrificed in the process. It is no longer “mixed”, it is simply painting.

Would you say that photography has gained in significance in your work when compared to the 1990s?

Yes, you could say that, but photography has always been important. Sometimes you feel it more, sometimes less, but it is always a means to help understand things.

Ambiguity and ambivalence are very characteristic of your work. This becomes obvious, for instance, when a painting appears in the background of another painting, as in this case …

…with the girl with the violin. That is a detail taken from Im freien Fall, which reappears as a background.

Similarly in Deux Amours, where a detail from Blind Date appears behind the two people in the portrait.

Yes, the picture in the picture. Art as a quotation is something that occurs frequently. My paintings are not true to perspective, on the contrary even, the motif at the back is larger than the real person in front. Valie Export and her husband are sitting in my studio, behind them stands the painting and this will be fed into the portrait – a picture in the picture. The things you find in the inserted picture are often larger than life compared to the people sitting in front.

The attributes one sees in your paintings are like secret codes.

Sometimes one can decipher them, but if they can’t be rationally decoded it’s just as well.

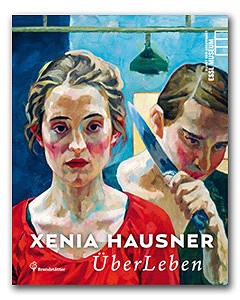

This ambiguity is also reflected by the title of the exhibition ÜberLeben.

The title is ambiguous – it is about survival and about life as such. The situations are deliberately ambivalent and fragmentary. Take Im freien Fall, where a figure is hanging into the picture from the top, and below her you see another figure who is grieving. You don’t know whether that person is falling down at that very moment and there is an emergency, or whether it is a carefully planned attack.

It’s very similar in Pensée Sauvage, where a very thrilling moment is suspended and one doesn’t know what will happen next.

It is a kind of slaughterhouse scene with a yearning for love. But there you are, it is not unambiguous. The slaughter knife is hanging on a tube and there are also two toothbrush mugs. Don’t ask me. I would completely screw up if I were to give a guided tour to visitors. The situation remains suspended and I am glad it does. The more ambivalence, the closer I am to the issue.

And this state of suspension is perfectly brought into play in the installation ÜberLeben at the Rotunda.

I hope so! This is a blast from my stage-designer days.

There is a couple consisting of two women, lying together peacefully, it seems – actually an idyllic scene. Above them, however, hangs a life-threateningly large, sharp-edged rock…

…and you never know whether the rock is going to drop, and what we see is a still of it falling. It is like a guillotine, a missile homing in on the idyll. It is the situation of threat or of not being prepared for disasters ahead. I don’t want to give it a current-affairs twist – but you could. We are confronted with humankind keeping its eyes shut although the writing on the wall is several meters high. It is an apparent idyll, one which we don’t know how long is going to stay that way, and with a very uncertain ending. The world is “slipping”. To that extent, the Rotunda provides a connection to the paintings: what is at stake – today more than ever – is the question of whether we will be able to survive.

How would you describe your development as a painter in recent years?

Painting involves something of a struggle for freedom and my kind of painting also relates to this liberating effect. When I got started, and that is a kind of evolution, my way of translating it was more refined. It is like working out to build some muscle. You have to watch yourself and not end up a narcissist, you hope. Once you spend a longer time painting it becomes clear that you would go about things differently today and you wonder: “Haven’t you been sloppy there, were you scared?”, or: “Will what you do now stand the test of time?”

You have three studios: in Vienna, in Berlin and one here in Traunkirchen.

Yes, it’s awful.

Where do you like working best?

No idea! At any rate there is too much erosion, too much friction loss on the journey to-and-fro. Berlin has this electrical connection with the world and art; you feel life hitting you full blast there – a real contrast to Austria. When I spend long enough admiring the Traunstein, I don’t care about Afghanistan any longer. Austria is a dangerously idyllic place!

Do you have any role models?

If you’re asking about my all time favorites in art history, the answer is Beckmann and Rembrandt. More contemporary: Rothko and Twombly. Remain open and work through, that’s what it’s all about. I also feel a thematic kinship to Borremans and Crewdson – especially in their puzzling strangeness and intrinsic vagueness.

How important is recognition by art collectors and curators, journalists and critics to you?

Every artist is sensitive or susceptible to praise or rejection. But you do what you have to do and keep your nose to the ground like a dog. At some point in time you will find your bone.

What are the hopes and expectations you have for this exhibition? How would you like the viewers to see, encounter and perceive your work?

I hope that the anecdotal curiosity for human interest stories, which you get so often with figurative painting, is on its way out. My work is supposed to prompt a discussion within the viewers. They should be positively shocked and affected and perhaps gain new insights. In brief, they should feel it touches and concerns them. If the paintings manage to do that, all’s well.

I think that is a very nice concluding statement. Thank you very much for this interview.