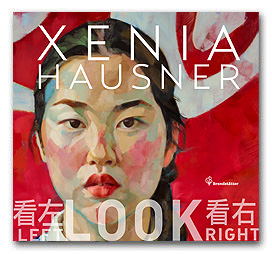

XENIA HAUSNER

Look Left – Look Right

Brandstätter Verlag, 2014

88 pages, 44 color illustrations

30 x 28 cm, hardcover

English / Chinese

ISBN 978-3-85033-841-7

With essays by Lars Nittve, Chang Tsong Zung, Catherine Maudsley and Connie Lam.

Chang Tsong-Zung

Xenia Hausner in China

Xenia Hausner’s incorporation of Chinese people and imagery into her signature style of portraiture seems to give a glimpse into the contemporary shape of this century-old dream. Her style of portraiture, a version of the intense expressionistic art informed by the angst of the war years in Europe, sets a period taste that turns the characters into products of history. Her Chinese and European figures, set in an essentially western art historical context, are presented in a strongly confrontational manner; the patches of intense colours that make their reality raw and abrasive expose the transitional state of existence in which her protagonists find themselves. Their lives appear to be haphazard and dishevelled. (…)

辛尼娅 候丝娜 在中国

辛 尼娅 候丝娜将中国的人物与意象融汇于她独具风格的绘画里, 似乎窥见了这个百年旧梦的当代形貌。她的画风,脱化白渗透着欧洲战乱年代之苦闷的强烈的表现主义艺术,从而树立起一种擬旧的趣味,将画中人变成了历史的产 物。她作品里的中国人与欧洲人,从西方主导的艺术史语境说来,是以极其对立的方式呈现的;令画中人的现实显得不加修饰、生硬粗糙的浓重色块,暴露了的主角 们身处的过渡性生存状态。其生活看上去随波逐流,混乱无序.

Lars Nittve

A Western Perspective, a Western Gaze

Now, when I sit down to actually write some paragraphs, it strikes me how difficult it is to have anything but a Western perspective. Not only for me – even though I truly believe that one only to a certain extent can transcend ones own cultural and intellectual horizon – but more importantly because the work of Xenia Hausner is so totally embedded in Western traditions. (…)

Then it does not matter whether the subjects or scenes of the paintings are European or, as in some rare occasions, South Asians or Chinese. They all feel – or is it look? – quintessentially Western – perhaps in the same way that another great painter, Claude Monet – made everything look quintessentially French, if not southern French. The light in his snow landscapes from Norway is for ever Mediterranean…

A western perspective, a Western gaze. It is unavoidable, and wonderful and a rather fitting celebration of the early arrival of Austria on this barren island in the South China Sea? (…)

Catherine Maudsley

The Universality of “Look Left, Look Right”

Xenia Hausner’s creative process is all-embracing and painstaking. It looks left and right; up and down, and it is not surprising that this global vision includes both Eastern and Western subjects and imagery. But it is the fundamental human condition which most concerns the artist. Of her paintings’ themes – loneliness, uneasiness, catastrophe and love – she says, “It is not my goal to present clear solutions, but to be precise in fragments whose mystery I am unable to solve.” Conveying ambiguity and tension are the hallmarks of her work.

In her studio, she recreates in flesh the scenes she has imagined in her mind. With the use of live models, materials she has collected on her travels and photographs which document what she has seen on her travels, she explicates the mystery. This often means juxtaposing time and place. (…)

Each artist’s vision and method is uniquely his or her own. Comparing Xenia Hausner’s paintings from “Look Left, Look Right” with specific works by Ai Weiwei (b. 1957), Liu Xiaodong (b. 1963), Wang Guangyi (b. 1957) and Zhang Xiaogang (b. 1958) illustrates the universality of the human concerns and experiences they each depict, as well as the varying approaches and methods. (…)

Asia in Xenia Hausner’s paintings

(…) As a traveler, the artist delves beyond the surface of whichever place she is visiting. She creates her tableaux, all of which are invented, not actual scenes, guided by a fertile imagination and painterly technique, and with a flair for composition. She doesn’t paint “en plein air”, but reconstructs scenes in her studio where she and a workshop team make extraordinary and exacting efforts. “Marking out the stage” is a familiar process for Hausner, who designed sets for nearly two decades. Her eye for colour, shape and form guide her to objects, including everyday ones, that have the qualities she seeks as an artist and appeal to her deep cultural curiosity.

A group of objects in “Crew Cabin” (2014) resonate with those in Zhang Xiaogang’s “Bloodlines” paintings: the red cord, here an electrical cord with an on-off switch, and a group of old black and white photographs. But this is where any resemblance ends. The female figure lying on the bed peers purposely and directly, challenging the viewer to alleviate the essential aloneness. Although placed in a grouping, the black and white photographs are of individual figures, highlighting each person’s solitariness. The carpet’s pattern is Chinese, and the patterning on the tabletop could suggest rattan. The green telephone, whose colour contrasts so strongly with the red bed cover and other red accents, is startling. Once belonging to a ship’s cabin, the telephone was found in a Hong Kong bric-a-brac shop. Theoretically, it allows communication with the bridge and other areas of the ship, but as an outdated, obsolete object, it dramatically emphasizes the aloneness of the cabin and its occupant.

(…) A definitive Hong Kong “foil” in Xenia Hausner’s paintings is the iconic pair, “Two Girls”. Dressed in traditional high-collared cheongsams, complemented by drop earrings, the demure young women smile, wear artfully applied makeup and have short bob-styled haircuts adorned with a spray of flowers. They were painted in the 1930s by Kwan Wai Nung (1878–1956), the king of calendar posters, who was commissioned by the cosmetic brand The House of Kwong Sang Hong. (…)

In “Saint Francis” (2013), two uniformed school girls sit in front of a massive “Coca-Cola” sign. Chinese artists Ai Weiwei and Wang Guangyi have responded powerfully to the omnipresence of this global soft-drink brand: Ai transforming ancient Chinese vases by painting the Coca-Cola logo on them and Wang by using it in his famous political pop painting “Great Criticism: Coca-Cola”. Like Ai and Wang, Hausner uses the logo to make a trenchant cultural and artistic statement.

Xenia Hausner and Contemporary Chinese Painting: Zhang Xiaogang and Liu Xiaodong

Zhang Xiaogang and Liu Xiaodong, two leading contemporary Chinese painters, are figurative painters in the way that Xenia Hausner is one. Zhang’s well-known “Bloodlines” series exposes fractured human relationships. Liu’s paintings such as his five-panel “Hotbed” (2005) depict disrupted lives.

Zhang Xiaogang’s work entered the world stage in 1994 with the São Paulo Biennial and came to even greater global attention in 1998 with the ground-breaking group exhibition Inside Out: New Chinese Art. Zhang’s “Bloodline: Family Portrait No. 2” from the mid-1990s startled viewers with its impersonal trio of an expressionless mother, whose face is rendered in flesh tone colours, and expressionless father, rendered in tones of grey derived from the studio photograph on which the painting is based. Their yellow-hued son is positioned between them. The three figures are linked by a red thread. The artist’s use of fine brushstrokes emphasizes the stillness of the scene.

Xenia Hausner is intrigued by Zhang Xiaogang’s “Bloodline” series because of the personal interrelationships it depicts and its message of alienation. Born just nine years after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, Zhang Xiaogang and others of his generation know alienation well. The Cultural Revolution, which lasted for a decade after its launch in 1967, was profoundly disruptive to families. It also prevented formal education from taking place. After the education system resumed, Zhang entered the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in 1977 and began to study oil painting in 1978. By 1992, he would visit his wife Teng Lei in Germany where Zhang would conclude, “I suddenly felt that the Chinese were too academic in their approach. We needed to draw upon the fundamental essence of life and living, not theories. What I had painted before was less about my life than escapist fantasies for my inner self. So I began looking at what was around me, the people, my friends.”

Liu Xiaodong studied at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, graduating from its oil painting department in 1988 and earning his MFA degree in 1995. China’s New Art, Post-1989, the 1993 exhibition which opened in Hong Kong before extensive touring overseas, featured two oil-on-canvas Liu Xiaodong paintings – his 1992 “City Hunter” and “Wedding Party”. “City Hunter” uses thickly applied paint and bold, expressive brush strokes, not unlike those favoured by Xenia Hausner. The catalogue comments: “His paintings are almost uncomfortable to look at: the images seem distorted, and there seems to be too much light, too much colour… Liu’s approach of utilizing a heightened existential awareness to get closer to the truth of objective reality enables the artist to achieve a compelling expression of the uncomfortable actualities of human existence.”

Liu’s engagement with social predicaments in his homeland can be seen in his paintings that focus on the human cost of building of the Yangzi River Dam. His engagement with issues beyond mainland China are evident in his multi-panel work, “Battlefield Realism: The Eighteen Arhats” (2004), which juxtaposes nine portraits of mainland soldiers and nine Taiwanese ones, communicating the universality of humanity, not political differences. In 2008, he depicted illegally dumped trash in Naples, Italy; in 2010 he turned to the theme of teen violence in America and in 2013 he painted for a month in the defunct Austrian mining town of Eisenerz.

Liu Xiaodong and Xenia Hausner, and many others beside them, exemplify the global fluidity and artistic engagement of twenty-first century artists. The inevitable question is: what does this global experience contribute to a contemporary artist’s work? (…)